|

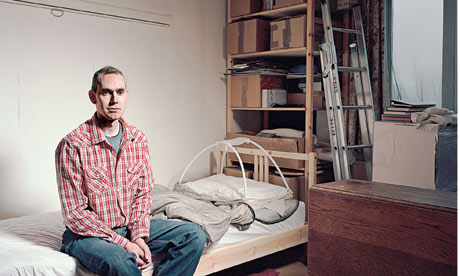

Tim Hallam, 36, sleeps in a custom-made silver-coated sleeping bag that helps block out electromagnetic fields. Photograph: Thomas Ball

|

Tim Hallam is just tall enough to seem gangly. His height makes the bedroom feel even smaller than it is. Muddy sunlight filters through the grey gauze hung over his window. His narrow bed appears to be covered with a glistening silver mosquito net. The door and the ceiling are lined with tinfoil. Tim tells me there is also a layer of foil beneath the wallpaper and under the wood-effect flooring. He says, "The room is completely insulated; the edges are sealed with aluminium tape and connected with conducting tape so I could ground the whole room. It's a Faraday cage, effectively. Grounding helps with the low frequencies radiation, apparently. The high frequencies just bounce off the outside."

Tim is trying to escape atmospheric manmade radiation caused by Wi-Fi, phone signals, radio, even TV screens and fluorescent bulbs. It's a hopeless task, he admits: "It's so hard to get away from, and it's taken a toll on my life." I offer to put my phone outside the room and he happily accepts, firmly closing the door. He explains the phone would have kept searching for a signal. "And because it wouldn't find one, it would keep ramping up." With the tinfoil inside his cage, the signal would hurtle around the room like a panicked bird.

Tim estimates he spent £1,000 on the insulation, taking photographs at every stage to share with others via ElectroSensitivity UK, the society for sufferers. He found the whole process stressful, especially after a summer sleeping in the garden of his shared house in Leamington Spa to escape a new flatmate's powerful Wi-Fi router. How did he feel about the flatmate at the time? "Oh, I hated him. It wasn't really him, of course. But I was so angry." Among the symptoms Tim experiences – headaches, muscular pain, dry eyes – there are memory lapses and irritability. He now says his bed is the single most important thing he owns. "I climb in and zip it up so I'm completely sealed. Inside, I sleep extremely well. Without it, my sleep is fragmented, and without sleep, then lots of other things go wrong."

Tim demonstrates the effectiveness of the tinfoil using a radiation detector called Elektrosmog, manufactured in Germany. It is blocky and white, which makes it look both retro and futuristic. On the front of the box, a picture of an electricity pylon is surrounded by jagged black lightning flashes. The machine gives a reading close to zero: Tim's room is radiation-free.

As a child in the 70s, I watched a BBC science-fiction serial called The Changes, which imagined a future after humans became allergic to electricity. Pylons were the greatest danger, making people violently sick. On cross-country runs, I would speed up when I had to pass beneath a power cable, feeling the weight of the buzzing electricity above me. The idea that electromagnetic fields affect our health took root in the 1960s. A US doctor named Robert O Becker became the face of the campaign against pylons after appearing on the US TV show 60 Minutes. Professor Andrew Marino, now of Louisiana State University, was Becker's lab partner. Marino says, "He's the reason nobody wants to live near power lines."

If electromagnetic radiation is dangerous to humans, there are far more risks now than 40 years ago, thanks to the telecommunications industry. More than a billion people worldwide own mobile phones. In the UK, there are more mobile contracts than people. The new 4G spectrum will cover 98% of the country, erasing all but the most remote "not spots".

Dr Mireille Toledano runs Cosmos, a 30-year, five-nation study into the effects of telecoms radiation on humans. She knows how rapidly things are changing. In 2000, a 10-year study into mobile phones and brain tumours pegged heavy use at 30 minutes a day. The study found the 90th percentile had spent 1,640 hours of their lives on their phones. In the UK, Toledano says, "heavy use is now defined at 86 minutes a day; 30 minutes is in the median range. Across the whole [international Cosmos study], the top 10% of users have now clocked up 4,160 or more hours."

The earlier study found no evidence linking phone use and cancer in the short term, yet as our love affair with technology keeps deepening, anxieties grow. Two years ago, the European Assembly passedResolution 1815, which, among other things, calls for restrictions on Wi-Fi in schools and the use of mobile phones by children. The World Health Organisation has classified electromagnetic fields of the kind used in mobile telephony as Group 2b carcinogens – that is, as possibly cancerous.

The issue of electromagnetic sensitivity is immediately political. It places sufferers on the other side from both industry and the governments that profit from leasing wavelengths. Over and over, I hear the phrase, "We are the canaries in the coal mine": sufferers believe we are approaching a tipping point. Tim Hallam worries about the effects of electromagnetic fields on the most vulnerable: on his sister's young family; on children in schools bathed in Wi-Fi rays; or old people in sheltered accommodation, each with their own internet router. "I think it's affecting everyone's cells. There are test-tube experiments which show it damages DNA and affects the blood-brain barrier. I do think there's going to be a surge in the people who are sensitive in years to come. But my sister's not fully taken that on board."

Yet electro hypersensitivity syndrome is controversial. Sweden recognises EHS as a "functional impairment", or disability, but it is the patients, not doctors, who make the diagnosis. The fact is, everyone who suffers from EHS is self-diagnosed – and each has their own story to explain the cause of their problems.

Tim was 16 years old, at a gig by the industrial band Sheep on Drugs, when the singer produced a pistol and fired blanks into the ceiling. Tim, who is now 36, says, "It was the loudest thing I had ever heard." His ears began ringing but he continued going to gigs without using ear plugs and the problem grew worse. He played clarinet in two orchestras but had to stop: "Immediately, my musical life and my social life ended." Today, his sister is a professional classical musician. Tim, a Cambridge graduate, is a van driver for Asda. He works shifts that allow him time alone when his flatmates are out and the house is free of Wi-Fi and phones. It was the arrival of Wi-Fi in his house, just 10 months ago, that led Tim to identify the cause of his problems, but it was the tinnitus that started it all.

|

| Michelle Berriedale-Johnson, 65, is wearing a jacket made from a silver-coated material that reduces the strength of electromagnetic fields. Photograph: Thomas Ball |

Michelle Berriedale-Johnson has worked in the field of food intolerances and allergies for more than 20 years. She runs the industry awards for "Free From" foods from her home in north-west London, as well as foodsmatter.com, a website that raises awareness around food intolerances. Five years ago, at the age of 60, she began to feel unwell. She was sitting at her desk when she identified the cause. "I looked up and there was the Royal Free Hospital with the phone masts on the top, beaming straight through my window, and it just clicked." Michelle is bright and lively, happy to dive beneath her desk to show the precautions she has taken to shield herself from the spaghetti of wires. Her walls are painted with carbon paint, lined with foil and papered over. The windows have the same netting as Tim's, though when she uses her Elektrosmog meter she discovers to her consternation that the netting is old and no longer works. Her front rooms buzz with electromagnetic radiation, though her office – now at the back of the house – shows far better readings. She says, "I'm lucky to work from home, but I often feel like a prisoner." When she leaves the house, she wears hats lined with material similar to Tim's mosquito netting and even has blouses made of the same material. "The important thing is to protect your head and upper torso," she says.

Michelle precisely identifies the moment she became sensitised to radiation. She was an early user of mobile phones. "Do you remember the type with the little aerial? I had one where the antenna had broken off, but I continued to use it pressed to my ear, which people who know tell me meant that I was using my entire head as an aerial." In her view, we are all sensitive to electromagnetic fields, but events can tip us over into hypersensitivity, like a kitchen sink filling so fast that the overflow becomes overwhelmed and water cascades to the floor.

The problem, in clinical terms, is that "hypersensitivity" refers either to allergies or to auto-immune conditions. EHS may be like hay fever or, in extreme cases, like rheumatoid arthritis but only via analogy. If we speak of "hypersensitivity" we are using a metaphor – or we are talking about something entirely new. Does this "new" condition exist?

Long-time researcher Dr Olle Johansson, from Sweden's Karolinska Institute, coined the term "screen dermatitis" to explain why computer users in the depths of the Stockholm winter could complain of sunburn-like symptoms. Johansson has a theory that could explain how extremely high levels of radiation could affect histamine levels in cells. Yet telecoms radiation is low and becoming lower as gadgets become more efficient. Johansson acknowledges that if anyone is found to be truly allergic to their phone it would be an entirely new kind of allergy, but he hopes that an awareness of EHS will lead to revolutionary changes. "In Sweden, we take accessibility measures seriously for disabilities. You think of changes to sidewalks, or wheelchair access, or ramps on buses. These are also helpful to mothers with prams, people with shopping or to rollerskaters. The big winner is everyone." Similarly, he believes that cutting off the telecoms signals would not only help EHS sufferers, it would benefit all of us, returning us to a society based on face-to-face human interaction.

Dr James Rubin of King's College Institute of Psychiatry is adamant EHS is not a genuine syndrome. "With most conditions, patients don't necessarily know what's going on. But with electrosensitivity there's an absolute certainty about the cause. Self-diagnosis is at the core of it." He prefers the term "idiopathic environmental intolerances", or IEI, which covers conditions with no obvious cause, like multiple chemical sensitivity, sick building syndrome, food intolerances – even a physical reaction to wind turbines. "The problem is, if you look for a coherent set of symptoms, you are not going to find it. You even find that people's symptoms change over time. Many have other intolerances in addition to the electrical sensitivity."

Tim is intolerant to milk and gluten. He is also allergic to wool, and cannot sleep in a room with a carpet. Michelle has no intolerances but admits she is unusual in the community: "Most people do." She made her diagnosis because she was familiar with EHS through her work. She is familiar with Rubin's research and has written blogs condemning his methods: "These stupid so-called provocation studies where they place a mobile in your hand and ask if you feel unwell. And if you say yes, they go, ho-ho, the phone wasn't switched on." These tests pay no attention to the way that people are sensitised, or react to their sensitivity in different ways, she believes.

Rubin is a bogeyman in the electrosensitive community thanks to a 2008 paper that suggested the condition was psychosomatic. Yet he has also undertaken a review of all the research – more than 50 provocation studies – and found no evidence of sensitivity to telecoms radiation. He says, "The suffering is very real – I don't doubt that – and I take it very seriously. But we've spent millions on the research and the time comes when you have to say, in the future the money would be better spent on looking for effective treatments, rather than chasing a cause."

Professor Andrew Marino is less sceptical. "When people say they feel unwell and trace that to a Wi-Fi signal or a phone, that is a kind of experiment. It may not be well designed, they may not understand blinds and double blinds, but if they are reasonable people, carefully noting what they are suffering, we should take a look at that."

Marino was a first-year postgraduate in 1964 when he began working with Dr Robert Becker. Once he and Becker began campaigning against electricity pylons, their funding disappeared. Becker retired at the relatively young age of 56. Today, Andrew Marino will not look to industry for research funds. He has reviewed many of the same 50 papers on EHS as Rubin, concluding, "It's easy to find nothing." The common denominator he identified in the papers casting doubt on EHS is that they were funded by the telecommunications industry.

EHS sufferers have criticised Rubin's research because it is funded jointly by mobile phone companies and government. They believe this shows direct bias. Marino's criticism is different. He recognises Rubin's money was placed in a fund and administered by scientists separate from the industry. Yet, he argues, the industry approves funding because statistical modelling of large-scale studies averages out experiences and produces no clear-cut results. Big business is happy to back risk studies, but they favour projects that minimise risk: "You look at the statistics and see the way they design the experiments and they have no ability to find anything."

Rubin's research is statistic-driven. If Rubin is a pollster, then Marino is a canvasser. He believes vast overviews hide the way people really feel. Marino chose to focus on a single sufferer, a female doctor. His two-week study began by first discovering which wavelengths affected her. Once her symptoms had subsided, Marino and his team began again, using provocation studies of real and fake signals. Their results were published as Electromagnetic Hypersensitivity: Evidence For A Novel Neurological Syndrome.

Marino and Rubin have exchanged a series of letters about the study in the Journal Of Neuroscience. If the research stands up, Marino's syndrome is novel because it is unlike other kinds of hypersensitivity. In truth, it depends upon singularity. Marino speaks urgently: "I'm not interested in measuring the prevalence of the syndrome. I want to establish its existence." In his view, humans – complex living organisms – are all different. In the economy of our bodies, Marino says, "causes becomes effects and effects becomes causes which become effects, and so on". It is an endless and unpredictable cycle.

So should we all make radical lifestyle changes, like cutting down our mobile phone use or getting rid of our Wi-Fi?

"Why?" Marino sounds perplexed.

"Because we might get sick."

Marino dismisses the idea. He may disagree vehemently with Rubin, but he views EHS sufferers as outliers, far removed from the average human experience and with few lessons for the rest of us. "Listen, I use an ear bud with my phone, and I minimise use. I don't know if you'd call it radical but I don't have acute reactions to anything. So there's nothing for me to worry about."

No comments:

Post a Comment